In this hot summer of discontent, I am running a hot socialist summer sale on annual subscriptions. As a reminder, subscriptions keep this newsletter running as one of the loudest, proudest, most politically feminist newsletters on Elon Musk’s internet.

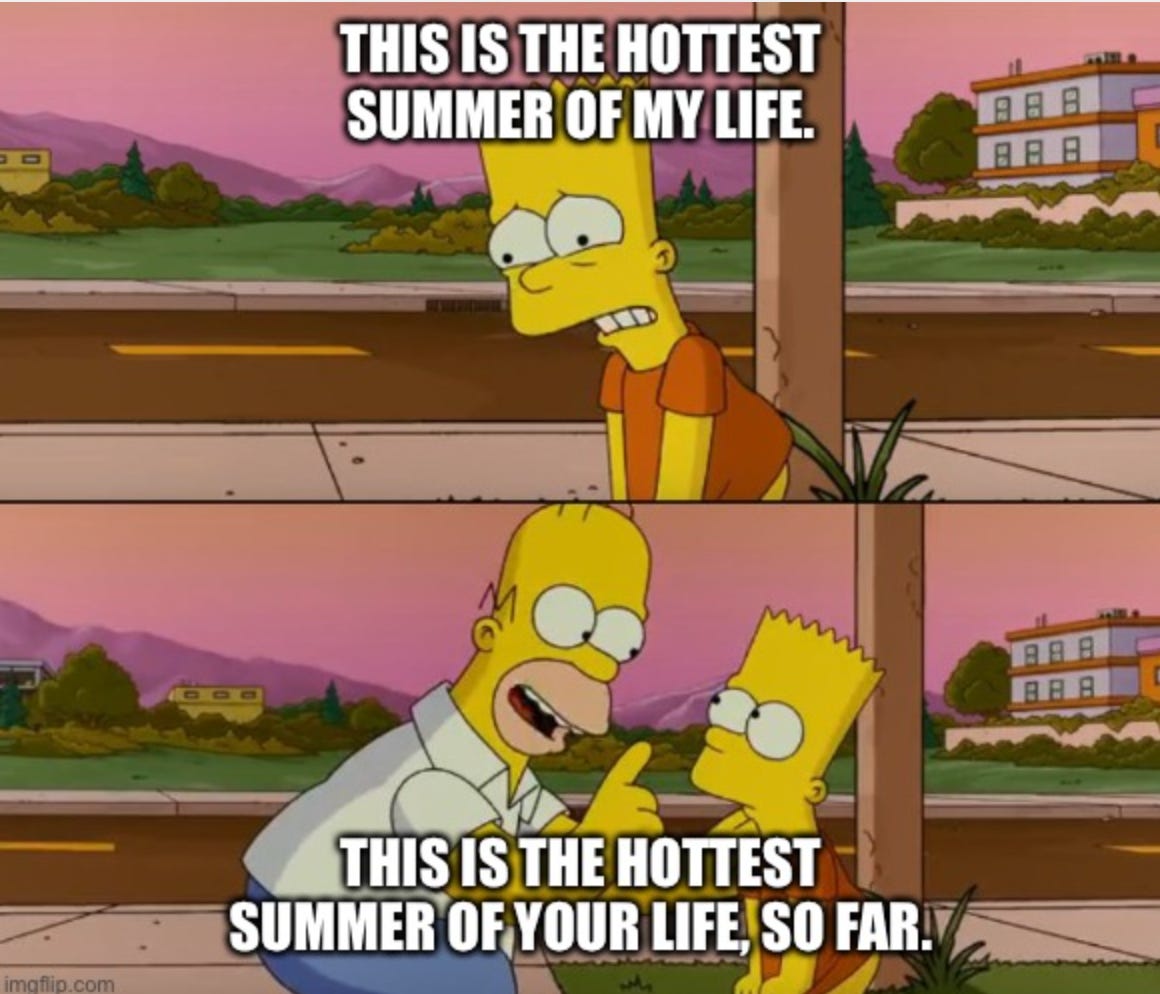

2025 is a hot summer in America. To paraphrase the Simpsons meme: one of the hottest summers of our lives so far.

The heat and the political turmoil feel different now than in 2020, which was a summer of primal screams, of our political discontent, of shouting for systemic change, of being locked inside and taking to the streets. That summer was hot asphalt and stifling masks. Demanding, pleading for institutions not to kill us and our neighbors.

This summer, we’ve lost so much and we continue to lose. But our screams feel different now. Tired feet back in the hot streets, smelling of tar and the closeness of bodies. Recycled protest signs. Hoarse voices pleading again for life over death. People are exhausted because, as the clichéd sign reads, we can’t believe we’re still protesting the same shit.

Maybe that’s because whatever allegedly ironclad dedication to systemic change was promised and pushed through promptly crumpled like tin foil. Hope and change run over by a desperate keening for the past. Any past.

The conventional wisdom is that as people get older, they will become more comfortable and more conservative. But millennial voters, voters born in the 1980s and ‘90s, are so far bucking that trend, aligning, by a few percentage points, with Democrats over Republicans. It’s not much, but it’s enough that trend forecasters are taking notice. Millennials, now aging, have seen the collapse of a financial system (multiple times), wars, historic elections, girl power to #MeToo to trad wife, the crime bill to racial reckoning to ICE deportations, same-sex marriage to trans healthcare bans.

In her book of essays I Want to Burn This Place Down, Maris Kreizman writes in a chapter titled “Neoliberalism and me” about going to see Bill Clinton speak in 1992 and believing so fully in the dream of neoliberalism. Believing that if she worked hard and and played by the rules, she too could be part of the American dream.

The opening is funny in the same way that reading a character in a novel write about how excited they are to take a trip on the Titanic is funny. The reader knows what’s coming. One big sad trombone doing the “whomp whomp” of history. Kreizman takes us from the hope of Clinton to the scandal to the 2000 financial collapse to the Brett Kavanaugh hearings. And then again to Clinton. Kreizman writes about how, when she decried Kavanaugh’s alleged behavior to Christine Blasey Ford, the online hordes pushed back and said, “Well, if you condemn Kavanaugh, you must also condemn Bill Clinton.”

Good. Done. “Sounds good to me,” Kreizman replies. If, upon consideration, those institutions we believed in failed us — if they were part of our oppression when we thought they were our liberation — then, fine, burn them to the ground.

Kreizman’s book is part of a cohort of books from Gen X and older millennial women rethinking ambition, the American Dream, and the promises we were raised with.

A generation of women raised on girl power who saw Hillary Clinton concuss herself on the glass ceiling, and Kamala Harris too, and all of us thinking, “Okay, now what?”

In this space are Jennifer Romolini’s Ambition Monster, The Myth of Making It by Samhita Mukhopadhyay, and Glynnis MacNicol’s I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself. Each a story of a woman pushing against the narrative of girl bosses and ambition and confronting the emptiness of the neoliberal dream.

Other books in this genre come at it slantwise. Sophie Gilbert’s Girl on Girl is a cultural examination of the world in which millennial and Gen X women grew up, charting both the rise of the girl boss and the emptiness and the frustration of clawing to the top. Because if you get there, you haven’t changed the world much; just played by rules never made for you in the first place. So what then?

It’s a conversation my friends and I are all having. When is enough enough? How do we be happy? Where does our ambition go when the world has made it impossible to have it all? Do we keep trying? Do we try something new? A whole generation of Paris Gellers crashing out, we tried to do everything right and still didn’t get where we thought we’d go. Not through lack of hard work or talent, but because these institutions were not designed for our life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness.

For Kreizman, the dream wasn’t complicated. Just a middle-class career in publishing, health insurance, and making books she could believe in. Then came the endless rounds of layoffs, the shitty pay, the revelation that the game is stacked in favor of those who already have money. But Kreizman doesn’t write about quitting in the same way as other cultural conversations around women and ambition.

She’s not saying, “The deck is stacked, so go be a trad wife.” None of the writers in this genre are. But there is a cultural push for that narrative. It’s present on social media and TikTok, in the insistence of princess treatment, the soft girl life, and, of course, the trad wife. Instead, Kreizman talks about agitating for change, unionizing, and demanding better wages.

Each of the essays in the book contends with an aspect of social, political and/or cultural change that Kreizman had to face and rethink, from insulin (Kreizman is diabetic) to the police (her twin brothers are cops), to kids (Kreizman and her husband, Josh Gondelman, are child-free).

I spoke with Kreizman before writing this essay, and I asked her how her ambition has changed as she aged. She told me she no longer has big ambitions for herself, but her ambition hasn’t gotten smaller; it’s gotten more encompassing. Now, she said, “I am ambitious for my community. My ambition is that I don’t want to see people die from a lack of insulin.”

It’s a reframing of ambition that is subtle and big-hearted, moving from the American dream of individual prosperity toward community survival.

Kreizman told me she was worried the book would be seen as “too angry.” The book seethes with a gentle anger, but it’s an anger built out of love, the tired kind of anger that wants everyone to be happy, to live, to experience a socialist revolution.

I asked Kreizman, a New Yorker, what she hopes her book brings to this hot political summer. And she said, “The best thing about having this book come out right this second, right now, is I look at my city, and last week, so many of us decided that the old ways weren't working. The Chuck Schumers of the world and the Democratic Party, as it stands right now, are just putting stuff out on social media and doing nothing. And that is not what most people want.”

“I see Zohran Mamdani capture so much of the imagination of people in my city,” Kreizman continued, “because he calls for change, but does it joyfully. And it's the best message to come out of that election. And what I want for this book.”

Now that’s ambition: to keep pushing for systemic change, despite all we’ve seen and witnessed, and to do with a smile — or, at least, with an endless capacity for joy.

Instead of going trad wife, my trans son and I are buying 37 acres of wooded land 30 mins out into the hills of the Northern Appalachians from our town. With cash, so we don't have financing to pay off. And, slowly but surely, we're going to build a common house, with kitchen and full bathroom, by the pond, then we'll spread out into the woods with little cabins and tent platforms. We have a small cadre of queer, creative, multi-racial folks who will put down some roots there and remember what it is to really live in community. Part-time, full-time-- whatever works for folks.

My ambition is to love on my people as well as I can and get to know a piece of land intimately. We'll be off-grid, but not dropped out. Just rebalanced, so the bulk of our attention is given to what is right in front of us. What we can touch and love and impact positively and continually.

Come visit, Lyz! We'll have a bonfire and sit in the wood-fired hot tub.

I have been thinking about this a lot. I was a go-getter, no job I can't do, bust my whole ass because I was told that rewards were waiting. Don't get me wrong, I have a decent life. I've been successful in both my day job field and my creative field, though not as successful in the latter as I'd hoped. But god, there are some days I feel like I did ALL THAT, at great expense to my health, and wonder what the fuck it was all for.