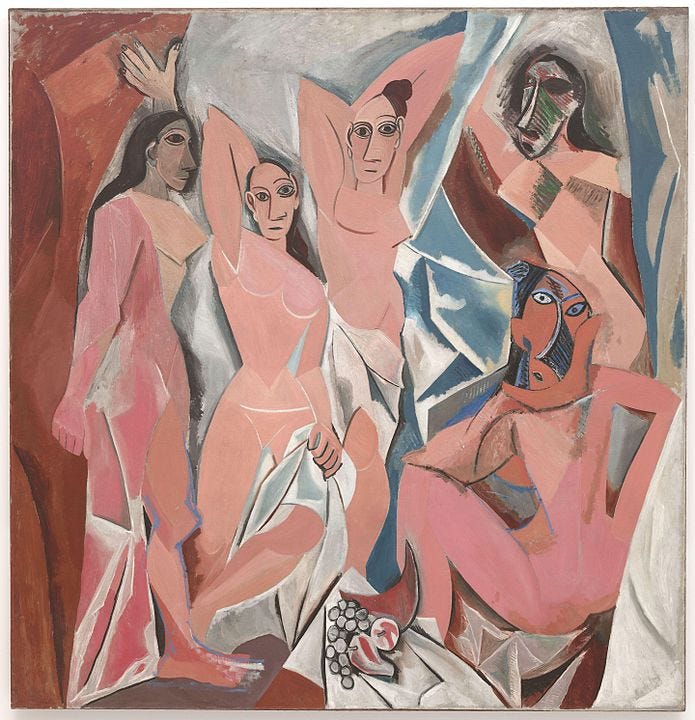

I recently went to the Art Institute of Chicago. The museum’s feature exhibit “Picasso: Drawing from Life” centers on the images that Pablo Picasso drew of his friends and lovers. Far from a solitary genius, Picasso could only be Picasso with the people around him the instillation argues.

I loved the way that the art just by the way it had been collected seemed to be in dialogue with the very idea of art. Creation for an artist can feel lonely. But it is truly a conversation that the artist is having with the world around her.

When I walked around the exhibit, I looked at all the faces Picasso had drawn and wondered how these friends and lovers felt about the genius. It also made me wonder how my friends felt about me. Who would be on my wall after I died?

The answer is so many people. But very specifically, my friend Anna. Anna is a Biblical scholar and professor whose area of interest is food and feminism. I’ve read every scholarly article she’s sent me. And her fingerprints are all over everything I’ve written.

This week, I texted Anna. I wanted to write about E Jean Carroll and the fight to make Trump pay for sexually abusing her. But what could I say that hadn’t been said? Anna told me about Sharon Marcus, a feminist theorist who argues that we need to change the very language of how we tell rape stories.

Marcus writes, “Rape engenders a sexualized female body defined as a wound, a body excluded from subject-subject violence, from the ability to engage in a fair fight. Rapists do not beat women at the game of violence, but aim to exclude us from playing it altogether.”

Marcus argues for a shift in the legal language, the descriptive language, and the way we teach women about fear and our bodies. Essentially, she seems to be arguing what Adrienne Marie Brown wrote about the limits of our language being the limits of our imagination. If we change the language, we can begin to change the story.

Marcus concludes, “In the place of a tremulous female body or the female self as an immobilized cavity, we can begin to imagine the female body as subject to change, as a potential object of fear and agent of violence.”

Reading all of this led me to write this for MSNBC:

In the stories we tell about rape, women are so often the objects of violence, lacking agency to stop it, subject to terror. Every woman, whether she’s been a victim of sexual abuse or not, has a story of fear, of walking alone at night with keys poised in her hands like tiny daggers, cold dread tickling her neck. Through these stories, even ones where there is a form of justice, women learn to be afraid. We walk through the world on unsteady feet, knowing that at any moment we could become victims of a crime for which there is little justice. In one moment, one night, the hands of one man, our bodies will be, we are told, ruined. In all of these stories women are disadvantaged, unable to defend ourselves. We are always the subject, never the actor, the one taking control of the narrative. And the men who abuse us are almost always invincible — rarely reported, rarely caught, rarely prosecuted.

But the story we are watching unfold with E. Jean Carroll is different. It is not one of determining guilt or innocence. It’s not even one of empathizing with a woman’s victimization or casting doubt on her story. A jury determined that Trump sexually abused her. And now, what we are determining is how much that will cost him.