Categorizing your Whites

An interview with Garrett Bucks about his new book and how he finds hope in the fight

This is the weekly edition of Men Yell at Me, a newsletter about the places politics and personhood meet. If you love this newsletter and find it thought-provoking, become a subscriber.

I first met Garrett Bucks when Anne Helen Petersen mentioned his newsletter in hers. Garrett lives in the Midwest, and his newsletter is a mix of the personal and political. It’s often very funny, but also challenging and searching. I subscribed immediately.

Garrett also founded and runs Barnraisers, a nonprofit that teaches people how to become organizers and change their communities for good.

Later, when I was looking for a partner to help me run a Discord community, I was emailing a lot of authors of political newsletters based in the Midwest (all run by men) and no one emailed me back. Or if they did, they were noncommittal and basically said, “If you do all the work, maybe I’ll join.” But Garrett saw what I was doing and emailed me. We had a phone call that was supposed to go one hour but lasted two and a half.

Together, we run the Flyover Discord, where we have over 1,000 members. I’ve learned so much from the way Garrett handles tense political conversations with kindness, openness, and absolutely no tolerance for guff.

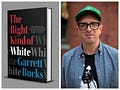

This month, Garrett published his first book, which is an extension of his work as an organizer and a writer. The Right Kind of White is an opening to a conversation about Whiteness, community, and justice. It’s funny, heartfelt, and expansive. But it also tolerates no excuses or defensiveness — not even in its author. As I followed young Garrett through his journey as the “good White guy,” it was impossible not to cringe a little, seeing my own sense of “good Whiteness” reflected back. But Garrett doesn’t allow the reader to wallow. “What next?” he challenges. Now that we see the problems and the systems we participate in, how do we change?

I spoke with Garrett about why he capitalizes the word “White” and why he’s hopeful for the future. Garrett and I will also be doing a joint book conversation in Omaha on April 17. Details are here.

Lyz: Why did you want to write this book?

Garrett: Eight years ago, after Trump was elected, hundreds of millions of White liberal Americans committed to resist, to make sure that the results of that election were never replicated. Four years later, America had a supposed “racial reckoning,” where millions of White people made similar commitments to fighting racism and white supremacy. And I don’t doubt the earnestness of those commitments. But we’re here today, in 2024, and Trump is once again the Republican nominee. Last year was the deadliest year for police killing of civilians in history. We’ve gone from putting books like How To Be Antiracist and Caste on the bestseller list to watching them get banned. So there’s clearly a disconnect. Whatever we — and here I’m talking about well-meaning progressive White people like myself — have been doing to be partners in building a more racially just country hasn’t been sufficient.

Now, I could have written a book that just tsk-tsked other White liberals for what they’re doing wrong. But that would have been dishonest. I spent a lifetime believing that, as a well-meaning White liberal, if I just read the right books and yelled loudly and had enough Black friends then I was “doing the work.” And it wasn’t until I began examining my relationship not just to Black, Brown and Indigenous communities but other White people as well that it started to click for me: “Oh, this is why I haven’t been all that useful!” and also, “Oh, this is why I’m so isolated from community.”

Lyz: Your book is an examination of Whiteness. What do people most misunderstand about Whiteness?

Garrett: There are so many different misunderstandings! But for now I want to focus on one that is still endemic among the type of “good, anti-racist” White people who already believe that power and privilege is real.

Here’s an anecdote that I think is pretty telling. Currently, as far as bookstores and libraries are concerned, The Right Kind of White is classified as an “African American studies” book. On Amazon, it’s even listed under “African American biographies.” Yikes! Why is that? Because there is no category for a book primarily about Whiteness. And that’s because the default assumption — even among White people who believe all the right anti-racist things — is that we can somehow defeat White supremacy without being curious about how it shows up in our own lives. We still believe there’s nothing to discover from excavating how and where we learned to be white; how we’ve reacted when we’ve noticed our Whiteness; and how those reactions have poisoned our relationships and our ability to build communities of care. We assume there’s nothing to see here!

Lyz: What was the hardest part of writing this book?

Garrett: There is a real need for those of us who benefit from oppressive hierarchies to learn how to share space and stop cutting to the front of every line. And because I do believe that deeply, I was very resistant to writing this as a memoir. I mean, it’s not exactly de-centering to put your whole life story down on paper. So I wanted to write a more distanced book, a safer book in a lot of ways. Something more academic.

But my editor really pushed me. He pointed out that White people’s default way of talking about each other is as a “them” rather than an “us” — unlike people from other racial groups. He argued that unless I was willing to tell my own story, I was still treating other White people as a “them.” That would have been the subtext if I had written this as a more sweeping historical narrative or as a public policy message book.

It was a compelling argument, but that didn’t make it easy. The more I accepted the challenge of memoir, though, the more that I realized that decentering yourself doesn’t just happen. You can’t just be like “Okay, I watched a TikTok from a Black activist and now I’ve experienced full ego death and am a fully humble amplification machine.” The weirdest, most unhelpful stuff we do as White people exists in us for a reason. And we won’t be able to get rid of it just by wishing it away. So there was real power in having to ask myself, “Why did I make my social justice work all about me for so many years? Where did that come from? How much was unique to my own biography and how much was all this junk around me — White supremacy, patriarchy and capitalism? And more importantly, what did it take to try something different?”

I’m still scared that I wrote a memoir. Of course there will be readers who are just like, “What’s so special about this particular White guy? I thought we were done having to listen to all these mediocre, privileged dummies.” My hope, though, is that it’s clear that the purpose of telling my story wasn’t that I think I’m a uniquely special White person, or a uniquely special man or straight person or middle-class person. It’s to model the role of self-examination in helping all of us grow into better community members and agents of social change.

Lyz: You have mentioned collaborating with your editor. What was that process like and did you ever have moments where you disagreed?

You mean like when I would say, “Nobody wants to hear a White guy talk about his feelings. This is going to read like a Noah Baumbach movie!” and my editor, Yahdon Israel, would reply, essentially, “Which Noah Baumbach movie features a model of a White man getting to the bottom of the ways he’s been addicted to white supremacy and patriarchy and offering an invitation to others stuck in the same ruts?”

Also, no disrespect to Noah Baumbach. He’s made some good movies. That scene in The Squid and the Whale at the museum rules.

It was such a gift to work with Yahdon. He wanted to help me to create a book that asks White people to read a story about ourselves with the same intentionality as we might give to a Between the World and Me or Minor Feelings. And he pushed me to stay true to that vision — to write a narrative that would draw people in and keep them reading in a way that most don’t with Big Message Books About Race. And I think that vision has paid off really beautifully.

And as long as there are more people to reach, more connections to make, more community to weave, that means that the choice isn’t between optimism and pessimism; it’s between isolation and relationship. And goddammit what a gift to choose relationships.

—

LL: Many people approach systemic problems with a sense of defensiveness.Part of your book seeks to dismantle this instinct in yourself and others. Why is that important?

Garrett: I’d argue that the desire to be a “good man” or “good White person” or a “good rich person” has stealthily done as much damage, both to individual relationships and to efforts for social change, as any other myth about privilege. I mean, let’s talk about what’s happening when our primary desire — as a person with a particular type of societal power — is to look good or be declared good by a woman or a person of color. You’re not actually caring about other people; you’re caring about yourself. And you’re also going to be artificially separating yourself from the very people with whom you should be figuring out all this nonsense.

One theme that became apparent over the course of writing this book was that, while I focused on what my desire to be the “right kind of White” was doing to my relationships with other White people (put simply, I made them my foils – proof of how much I had conquered my racism by comparison), I was also tokenizing people of color in my life. I wasn’t really interested in what their needs might be in relationship with others; I was obsessed with what their validation or friendship meant for me.

When you zoom out from this,you see a key to that question I posed at the beginning of our interview: “Why have well-meaning White people made so little progress toward racial justice? Why haven’t men made much progress towards dismantling patriarchy — both societally and in our relationships?” Well, at least in part, because those of us who claim to be animated to change things actually haven’t been trying much at all. We’ve been too obsessed with trying to make ourselves look good.

LL: Why do you capitalize White in the book?

I was originally inspired by Eve Ewing’s essay “I’m a Black Scholar Who Studies Race. Here’s Why I Capitalize White.” Put simply, I think it’s important to hold two truths at once. Whiteness isn’t real. It’s an invented grab-bag that various ethnic groups were assimilated into in order to justify dominance. But we now have hundreds of years of collective experience being White, and while that’s not a positive legacy, it is a shared history. For me, capitalizing White is a reminder to myself and other White people that there’s no escaping the legacy of White supremacy alone. This is our mess, together. And that’s both terrible news but also really wonderful news — thank God I both can’t and shouldn’t pretend to be able to solve racism alone.

LL: Your book is hopeful at the end that there is a way through. In a time when people struggle with despair, what gives you hope?

Garrett: Oh my goodness, I’m so hopeful! Because I’m just so alive to the fact that we can’t declare failure yet because we (and here I mean White people) have never really tried to dismantle White supremacy. Men have never really tried to dismantle patriarchy. Americans have never really tried to build an economic system more liberating than capitalism. And we’ve definitely never committed our lives, collectively, to organizing with each other to make that happen.

Not to give away the end of the book, but while I spent a lot of my life artificially isolating myself from other White people, by the end of the story I’m reaching out and connecting with people across the country who have the same anger, the same sorrow, and same desire for something better than me. I’m coaching and learning from organizers in New Orleans and Council Bluffs and Brooklyn and Boise. And collectively, we’re all trying to do things we wouldn’t have done a few years previously — talking to the other parents at pickup about funding equity for schools, hosting a neighborhood potluck to brainstorm how we can take care of each other without relying on cops, canvassing in rural and exurban districts that are assumed to be conservative, but partially because the Democratic party gave up trying to win them back. And isn’t that where hope comes from? Connection and action! Forward movement. Remembering that, contrary to the myths of White supremacy, patriarchy and capitalism, we can’t get to the promised land alone.

This isn’t to downplay the scale of the work ahead of us, nor its urgency. That four-headed hydra of White supremacy, capitalism, patriarchy and heterosexism claims more victims every single day. That’s the tragic news. I’m not hopeful because I’m plunging my head in the sand. I’m hopeful because the world is full of billions of people who both deserve and want something better than this — including people who benefit from the current system. And as long as there are more people to reach, more connections to make, more community to weave, that means that the choice isn’t between optimism and pessimism; it’s between isolation and relationship. And goddammit what a gift to choose relationships.

I pre-ordered Garrett's book. It arrived last week and, I’ll confess, it’s still sitting in its box on my dining room table. Part of the why is that I’m working three jobs, raising two kids and managing a house alone. But the other part is that I know it will be confronting and I want the space and time to be confronted.

Which a very convenient way to avoid the actual confrontation, I’m realizing. Because there’s never sufficient time to confront your own complicity in oppressive systems unobstructed. What would that take? Well, Whiteness has been constructing and fortifying itself for several hundred years now…

So, I’m gonna open that box when I get home and get it started. All we can do is begin.

I am excited to read this book. I have put an immense amount of effort into evolving myself, but I don't really have that White community to check in with because folks just don't talk about Whiteness except to use whatever the latest buzz words are. What I do see are my friends who are people of color, Indigenous, Black - increasingly frustrated with White people, especially allies, for not recognizing so, so much.